Charted breaths.

Mapped periods from various texts.

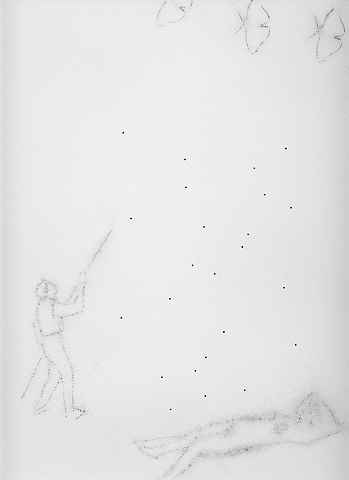

As pure exercise a few years ago I began borrowing images from various resources with the intention of creating my own narratives with them. Using a *pounce wheel I transferred figures, birds, moths, structures and forms from the pages of various art books. Each image was made up of a string of small, punctured dots. While pouncing the stars from a Jasper Johns painting my eyes were guided to the small periods buried within the text on the page.

I’ve now turned solely to books, poetry, letters and notes- received, written, found. Some charted and destroyed. My attention is not only towards the words, but upon the moments between the thoughts, at the breath. The periods. When words are removed a pattern of pauses emerges and surrenders to a predestined design born solely from missing words. The first book to be charted in its entirety was “The Paradiso, by Dante Alighieri”. Newly discovered constellations were unleashed through the text of a 1904 edition. Thirty three "drawings" from Dantes very own heaven come to life in the dark as the charted periods are revealed in tiny beads of glow paint. Many written letters and poems are charted and destroyed, leaving only the template of the periods to be explored in various context.

As for the work in general, the charted text will sometimes never be revealed. It's often just not necessary. Or rather the idea of not revealing their truth is something that interests me these days. While any text I chart has significance in meaning, and to the process- it is not significant to the experience of viewing the work. Or perhaps it is. But I want to hold the power in revealing it, or not. Each panel is simply what's left after the song is over. It's essence. Rarely does anyone remember the words anyway. Only the melody.

*pounce wheel; Pounce bags are commonly used in conjunction with pounce wheels to transfer drawings from one surface to another. The toothed pounce wheel is used to perforate the lines of a drawing with small, evenly spaced holes, and then the pounce bag is used to dust those perforations, effectively transferring the design or pattern to the surface beneath.

Review by Jack Livingston, Executive Editor of RADAR

“Light”, Exhibition at Gallery 4

…Constellation Scripture Dante Code

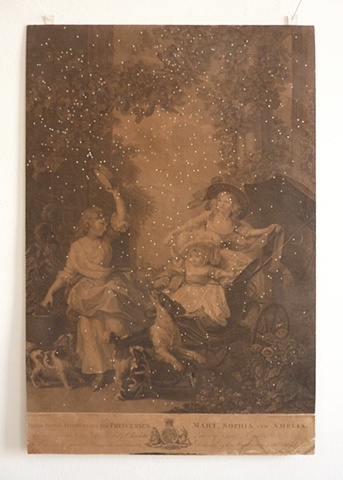

Holding court, running the length and backstretch of the long central gallery wall is an expansive dark line of 33 sumptuous black paper rectangles. When you get within a few feet of the work the concentrated configurations of small dots of white paint strewn strategically across the paper suddenly become apparent. This is the work of Jacqueline Skaggs.

Ones first assumption is one is looking at star constellations. Sections of the celestial night sky. Heaven above. And in a manner of speaking one would be correct. But the constellations are poetic and of this earth not the ones of true astronomy. They are constellations held within the pages of The Paradiso of Dante Alighieri.

Prayer to the Virgin (Paradiso, Canto 33)

Virgin mother, daughter of thy son, lowly and

uplifted more than any creature, fixed goal

of the eternal counsel,

thou art she who didst human nature so

ennoble that it’s own Maker

scorned not to become its making.

In thy womb was lit again the love

under whose warmth in the eternal peace

this flower hath thus unfolded.

Here art thou unto us the meridian torch of

love and there below with mortals art a

living spring of hope.

From The Paradiso of Dante Alighieri

Ah, the paradise of Dante. Most people go for the darkside, the Inferno. This book, the final of the famous visionary trilogy; one on hell, one on purgatory and finally the last rhapsody laden one on heaven. It is interesting Skaggs chose book three, the book of redemption, the book of light. This thick poetic song text emphasizes light as symbolic of truth. The truth of Dante's catholic God saving him from the carnage he has witnessed below. Celestial objects abound through out this part of the trilogy as does love and a sense of emanating glory.

And how does Jacqueline chart this classic potentially overwrought poetic territory? Using a particular addition of the book, she created graphic templates of each page by marking the tiny circular periods as they actually physically appear across the text. Using the templates she transfers the periods as white paint dots to a lush black background. She transfers all pages of a single canto to one painting. This exhibit presents her representation of the Paradiso cantos in full, 33 total. Three hundred plus pages of actual text were used.

In Skaggs version three hundred plus pages of text were also vanquished. Only the breath stops remain. In this there is a passing reference to semiotics and the importance of notation-signage as well as a nod to the breath notion in Buddhist practice.

The staggering complex Morse code multiple constellation like interpretive resonance of Skaggs endeavor is rooted in her sense of combining the sublime poetic with purist painting. She is one of those artists who manage to keep a clear clean balance between the two. There is always something behind the beauty. She says she uses a personal psychological hook on which to hang her work and is not at all averse to the spiritual and the elegance of her natural style. There is no wavering here. It is all clarity and bold balance.

Skaggs has found a way in these small paper paintings to minimally express literal volumes. The 33 paintings, when not on the wall sit as an actual handsome boxed volume, which can be 'read' page by page. In the end the paintings return to their roots - the intimate book format.

The current vogue for conceptual based formal art in the United States maybe a reaction to the dominance of overly sensational and highly emotive works of the past decades Euro pop invasion. In some ways U.S. conceptualist fervor seems positively puritanical by comparison. Of course this analysis is simplistic.

Sol Lewitt stated once in interview how the art audience could choose their approach to the then new and confounding minimalist works. They could just accept the objects as they were, reductive in the extreme or if they had the fortitude and desire they could look for the clues, unearth the keys and unlock the so-called minimal works thus revealing their rich and often complicated conceptual nature.